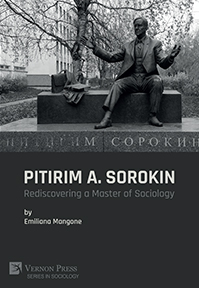

The following monograph has just been published:

Pitirim A. Sorokin: Rediscovering a Master of Sociology

by Emiliana Mangone

Vernon Press, 2023

More information is available at

https://vernonpress.com/book/1812

The following is a synopsis by Olga A. Simonova, Academic Supervisor of the School of Sociology at the National Research University, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia:

This book is a historical and sociological study of the ideas of the outstanding Russian American sociologist Pitirim Sorokin. In a relatively small book (which is its undoubted virtue), his ideas are presented in a clear manner, along with biographical facts. The book consists of three parts and eight chapters. At the beginning, we are introduced to a biographical lapidary sketch, which the author justifiably divides into two main parts – the Russian period and the American period, which is not a simplification but makes the perception of the development of the social thinker’s ideas clearer and more coherent. Then some works of the American period are disclosed, including very controversial ones, including the general theory of socio-cultural dynamics by Sorokin, which is one of the most important theories of cultural development in the twentieth century. In the third part, the author considers Sorokin’s ideas, first of all, those of altruistic love, in the context of global problems, conflicts, and catastrophes.

The book is valuable for the younger generation of sociologists, as it addresses the rediscovery of the ideas of the classic sociology, which have been undeservedly forgotten or ignored in research and publications. In this way, the book contributes to the continuity of sociological theory and sociological education. Today Sorokin’s ideas have become relevant and even topical again since Sorokin, as the author points out, was formed as a scholar in an era of social upheaval in Russia and became a prominent theorist of revolution and

humanitarian catastrophes and at the same time a scholar who passionately sought a way out of the crisis of modern civilization through a revival of altruism and brotherly love. Throughout the book Emiliana Mangone solves several sociological “puzzles”: why the Russian-born social thinker had such an impressive career, why he remained a “stranger” in American sociology, why he turned to “positive” social phenomena – solidarity, altruism, brotherly love, friendship, the revival of spiritual values – even though he witnessed dramatic social and political events.

The book is a truly fundamental study – it fully and clearly presents Sorokin’s theory and methodology in the form of an integral picture of culture and society and a mixed integral method of research, establishes the connection between Sorokin’s ideas and other sociological traditions, reveals interesting biographical facts (in particular, in a very interesting chapter on Sorokin and Talcott Parsons’s relations, which are considered not in terms of sympathy and antipathy but in terms of development of sociological knowledge and institutionalization of the discipline), and is based on the most important sources on Sorokin’s work.

The author of the folio observes all the norms of academic ethics and neutrality, so the book is genuinely interesting. Much about Sorokin’s work and his biography is already known, but the book is of interest to Russian researchers, too, who often miss the details of the American period of his career. The fundamental novelty of this book is the consideration of Sorokin’s work in the contemporary global context – global crises, epidemics, and war, which is obviously necessary for all and not only for sociologists.